- AVANT-PROPOS

- FOREWORD

- PROGRAMME DU COLLOQUE

SYMPOSIUM PROGRAMME

- ACTES DU COLLOQUE - VERSION FRANÇAISE

- OUVERTURE DU COLLOQUE :

M. JEAN-FRANÇOIS RAPIN, PRÉSIDENT DE LA COMMISSION DES AFFAIRES EUROPÉENNES

DU SÉNAT FRANÇAIS

- SESSION 1

LE CONTRÔLE PARLEMENTAIRE DE LA POLITIQUE EUROPÉENNE DES GOUVERNEMENTS

- I. INTRODUCTION

M. Jean-François Rapin, président de la commission des affaires européennes

- II. CIRCUITS NATIONAUX DE CONTRÔLE

PARLEMENTAIRE DANS L'UNION EUROPÉENNE VERS UNE CONVERGENCE DES

MODÈLES DE CONTRÔLE ?

Mme Elena Griglio, fonctionnaire du Sénat italien, professeure associée à l'Université Luiss Guido Carli de Rome

- 1. Introduction. Le circuit national du

contrôle parlementaire des affaires européennes et ses effets

extraterritoriaux

- 2. Quel impact le contrôle des affaires

européennes par les parlements nationaux peut-il avoir ? Les

facteurs contextuels européens et nationaux

- 3. Comment les parlements nationaux

façonnent le contrôle des affaires européennes : les

principales options disponibles

- 4. Modèles de contrôle dans une

perspective dynamique : comment les parlements nationaux réagissent

aux changements majeurs dans le cadre de l'UE

- 5. Les conclusions

- 1. Introduction. Le circuit national du

contrôle parlementaire des affaires européennes et ses effets

extraterritoriaux

- III. LE CONTRÔLE PARLEMENTAIRE DE LA

POLITIQUE EUROPÉENNE DU GOUVERNEMENT EN FRANCE : TENDANCES

ET ÉVOLUTIONS

M. Didier Blanc, professeur de droit public à l'Université Toulouse 1 Capitole, IRDEIC

- IV. LE CONTRÔLE PARLEMENTAIRE DE LA POLITIQUE

EUROPÉENNE DU GOUVERNEMENT EN SUÈDE : LE RÔLE DE LA

COMMISSION DES AFFAIRES EUROPÉENNES DU PARLEMENT SUÉDOIS

Mme Johanna Möllerberg Nordfors, cheffe du secrétariat de la commission pour l'Union européenne du Parlement suédois

- V. COMMENT RENDRE LE CONTRÔLE PARLEMENTAIRE

DE LA POLITIQUE EUROPÉENNE PLUS EFFICACE ? AVANTAGES ET

INCONVÉNIENTS DU SYSTÈME DANOIS

Mme Lotte Rickers Olesen, Représentante du Parlement danois auprès des institutions européennes

- I. INTRODUCTION

- SESSION 2

LE RÔLE DES PARLEMENTS NATIONAUX

DANS LE PROCESSUS DÉCISIONNEL EUROPÉEN

- I. INTERVENTION DE M. GÉRARD LARCHER,

PRÉSIDENT DU SÉNAT

- II. INTRODUCTION

M. Pierre Laurent, vice-président de la commission des affaires européennes du Sénat français

- III. LES INTERACTIONS ENTRE LES PARLEMENTS

NATIONAUX ET LES INSTITUTIONS DE L'UNION EUROPÉENNE : UN PANORAMA -

M. Olivier Rozenberg, professeur associé à Sciences

Po

- IV. PARLEMENTS NATIONAUX : COMMENT PASSER

D'UN POUVOIR

DE VETO À UN RÔLE PROACTIF ?

Mme Katrin Auel, professeure associée à l'Institut d'études avancées de Vienne

- V. LES CONSÉQUENCES POUR LES PARLEMENTS

NATIONAUX DU RÔLE CROISSANT DE L'UNION EUROPÉENNE SUR LES SUJETS

D'UNION ÉCONOMIQUE ET MONÉTAIRE ET LES MOYENS DE S'Y

ADAPTER

M. Gavin Barrett, professeur à l'University college Dublin

- VI. LES PARLEMENTS NATIONAUX ET LE PROCESSUS

DÉCISIONNEL EUROPÉEN PENDANT L'ÉPIDÉMIE DE

COVID-19

Mme Christine Neuhold, professeure à l'Université de Maastricht

- I. INTERVENTION DE M. GÉRARD LARCHER,

PRÉSIDENT DU SÉNAT

- SESSION 3

LA COOPÉRATION INTERPARLEMENTAIRE

AU NIVEAU DE L'UNION

- I. INTRODUCTION

M. Didier Marie, vice-président de la commission des affaires européennes du Sénat français

- II. LA COOPÉRATION INTERPARLEMENTAIRE AU

NIVEAU POLITIQUE ET ADMINISTRATIF, DANS LE SYSTÈME

PARLEMENTAIRE EUROPÉEN

M. Nicola Lupo, professeur de droit public à l'université Luiss Guido Carli de Rome, ancien fonctionnaire de la Chambre des députés italienne

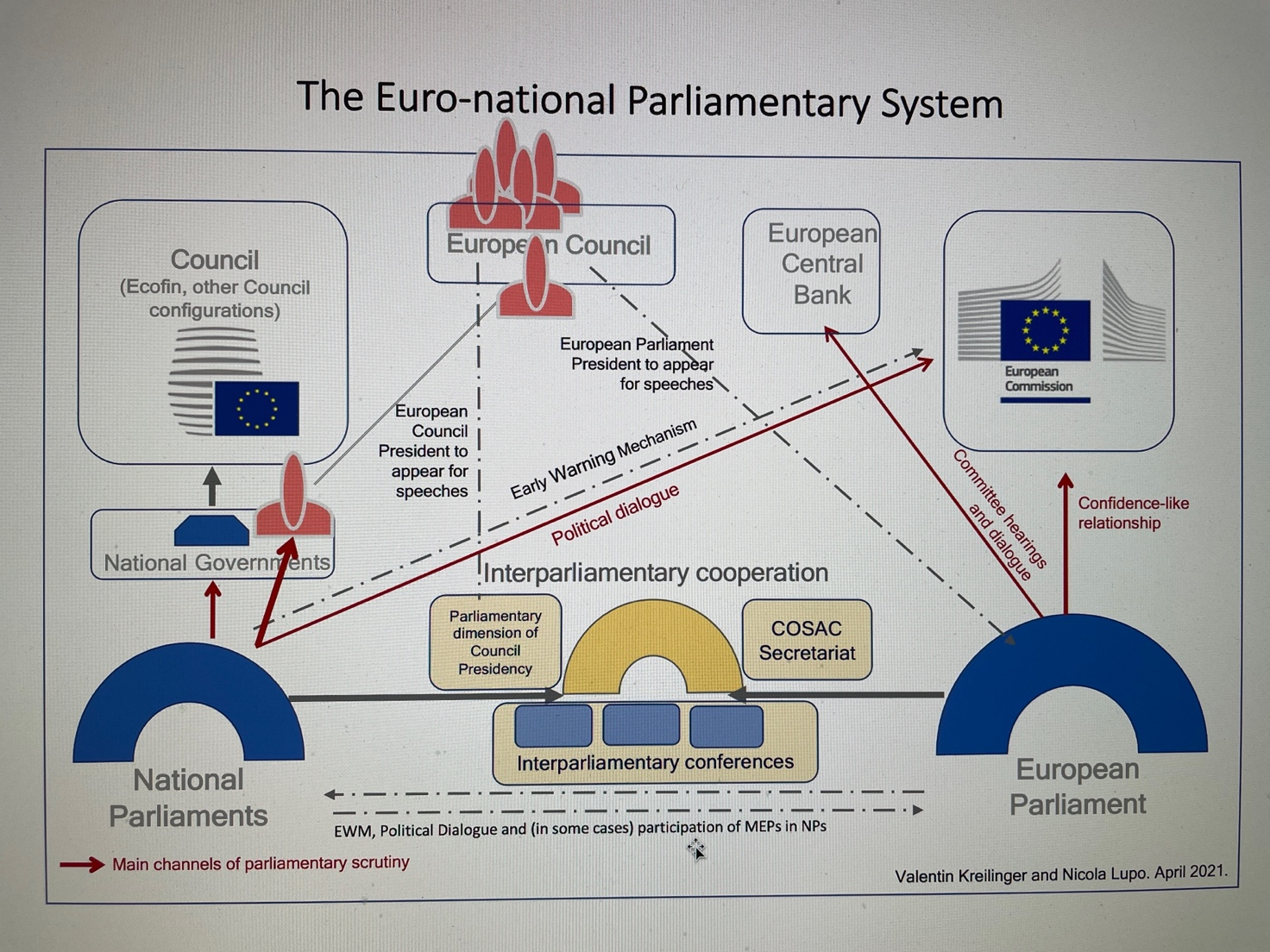

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Le concept de système parlementaire

euro-national

- 3. Les fonctions de la coopération

interparlementaire dans l'Union européenne

- 4. Les différences entre la

coopération interparlementaire au sein de l'UE et la diplomatie

parlementaire

- 5. Le débat sur la dimension administrative

de la coopération interparlementaire

- 6. Les effets de Covid-19 et de la

possibilité d'avoir une activité parlementaire

« à distance »

- 7. Les effets des accords bilatéraux entre

États membres et d'une Europe plus asymétrique

- 8. Conclusion

- 1. Introduction

- III. BILAN ET FUTUR DE LA CONFÉRENCE

INTERPARLEMENTAIRE SUR LA STABILITÉ, LA COORDINATION ÉCONOMIQUE

ET LA GOUVERNANCE, UNE DÉCENNIE APRÈS SA

CRÉATION

Mme Diane Fromage, chercheuse individuelle Marie Sklodowska-Curie

- IV. FUTUR DE L'EUROPE : POURQUOI IL FAUT UNE

SECONDE CHAMBRE AU SEIN DE L'UNION

EUROPÉENNE

M. Guillaume Sacriste, maître de conférences en science politique à l'Université Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne, CESSP

- I. INTRODUCTION

- SESSION 4

CONSTITUTIONS, DOMAINE RÉGALIEN

ET DROIT EUROPÉEN

- I. INTRODUCTION

M. Jean-François Rapin, président de la commission des affaires européennes du Sénat français

- II. L'IDENTITÉ CONSTITUTIONNELLE ET LA

COUR DE JUSTICE DE L'UNION EUROPÉENNE

Mme Laure Clément-Wilz, professeure de droit public à l'Université Paris Est Créteil

- III. LE TRIBUNAL CONSTITUTIONNEL POLONAIS ET

L'UNION EUROPÉENNE

M. András Jakab, professeur de droit constitutionnel et administratif à l'Université de Salzbourg

- IV. DOMAINES CONSTITUTIONNELS ESSENTIELS ET DROIT

EUROPÉEN : LES EXPÉRIENCES ALLEMANDES

M. Mattias Wendel, professeur de droit public à l'université de Leipzig

- V. À LA RECHERCHE DE SOLUTIONS AUX CONFLITS

ENTRE LES IDENTITÉS NATIONALES ET LES RÈGLES ET PRINCIPES

EUROPÉENS

M. Bertrand Mathieu, professeur de droit public à l'Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, Conseiller d'État en service extraordinaire

- I. INTRODUCTION

- CLÔTURE DES TRAVAUX :

M. Jean-François Rapin, président de la commission

des affaires européennes du Sénat français

- SYMPOSIUM PROCEEDINGS - ENGLISH VERSION

- SYMPOSIUM OPENING

MR JEAN-FRANÇOIS RAPIN, CHAIRMAN OF THE EUROPEAN AFFAIRS COMMITTEE

OF THE FRENCH SENATE

- SESSION 1

PARLIAMENTARY SCRUTINY

OF GOVERNMENTS' EUROPEAN POLICY

- I. INTRODUCTION

Mr Jean-François Rapin, Chairman of the European affairs committee of the French Senate

- II. NATIONAL CIRCUITS OF PARLIAMENTARY SCRUTINY

OF EUROPEAN UNION AFFAIRS: TOWARDS A CONVERGENCE OF THE SCRUTINY MODELS?

Ms Elena Griglio, Parliamentary Senior Official of the Italian Senate and Adjunct Professor at Luiss Guido Carli University in Rome

- 1. Introduction: The national circuit of

parliamentary scrutiny of EU affairs and its extra-territorial effects

- 2. What impact can national parliaments' scrutiny

of EU affairs produce? The European and national contextual factors

- 3. How national parliaments shape the scrutiny of

EU affairs: the main options available

- 4. Scrutiny models from a dynamic perspective: how

national parliaments are reacting to major changes in the EU framework

- 5. Conclusions

- 1. Introduction: The national circuit of

parliamentary scrutiny of EU affairs and its extra-territorial effects

- III. PARLIAMENTARY SCRUTINY OF THE FRENCH

GOVERNMENT'S EUROPEAN POLICY: TRENDS AND DEVELOPMENTS

Mr Didier Blanc, University Professor, Toulouse 1 Capitole University, Institute for Research in European, International and Comparative Law (IRDEIC)

- IV. PARLIAMENTARY SCRUTINY OF THE SWEDISH

GOVERNMENTS' EUROPEAN POLICY: THE ROLE OF THE EU COMMITTEE IN THE

SWEDISH PARLIAMENT

Ms Johanna Möllerberg Nordfors, head of the secretariat of the European Union Committee of the Swedish Parliament

- V. HOW TO MAKE PARLIAMENTARY SCRUTINY MORE

EFFECTIVE? AVANDAGES AND DISAVADVANTAGES OF THE DANISH SYSTEM

Ms Lotte Rickers Olesen, Permanent Representative of the Danish Parliament to the European Union

- I. INTRODUCTION

- SESSION 2

THE ROLE OF NATIONAL PARLIAMENTS IN THE EUROPEAN DECISION-MAKING PROCESS

- I. ADDRESS OF MR GÉRARD LARCHER, PRESIDENT

OF THE FRENCH SENATE

- II. INTRODUCTION

Mr Pierre Laurent, Deputy Chair of the European affairs Committee of the French Senate

- III. INTERACTIONS BETWEEN NATIONAL PARLIAMENTS AND

THE INSTITUTIONS OF THE EUROPEAN UNION: AN OVERVIEW - Mr Olivier

Rozenberg, Professor, Sciences-Po, Centre for European studies and comparative

politics

- IV. HOW CAN NATIONAL PARLIAMENTS MOVE ON FROM A

ROLE OF VETO PLAYER TO A PROACTIVE ROLE?

Ms Katrin Auel, Associate Professor at the Institute for advanced studies in Vienna

- V. THE CONSEQUENCES FOR NATIONAL PARLIAMENTS OF

THE INCREASING ROLE OF THE EU ON EMU TOPICS AND THEIR ADAPTATIONS

Professor Gavin Barrett, University college of Dublin

- VI. NATIONAL PARLIAMENTS AND EUROPEAN

DECISION-MAKING DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

Professor Christine Neuhold, Maastricht University

- I. ADDRESS OF MR GÉRARD LARCHER, PRESIDENT

OF THE FRENCH SENATE

- SESSION 3

INTERPARLIAMENTARY COOPERATION

AT UNION LEVEL

- I. INTRODUCTION

Mr Didier Marie, Deputy Chair of the European affairs Committee of the French Senate

- II. INTERPARLIAMENTARY COOPERATION AT THE

POLITICAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE LEVELS, IN THE EURO-NATIONAL

PARLIAMENTARY SYSTEM

Mr Nicola Lupo, Professor of Public Law, Luiss Guido Carli University, Rome

- 1. Introduction

- 2. The concept of the Euro-national parliamentary

system

- 3. The functions of interparliamentary cooperation

in the European Union

- 4. The differences between interparliamentary

cooperation in the EU and parliamentary diplomacy

- 5. The debate on the administrative dimension of

interparliamentary cooperation

- 6. The effects of Covid-19 and of the possibility

of having some “remote” parliamentary activity

- 7. The effects of bilateral agreements between

Member States and of a more asymmetrical Europe

- 8. Conclusion

- 1. Introduction

- III. ASSESSMENT AND FUTURE OF THE

INTERPARLIAMENTARY CONFERENCE ON ECONOMIC STABILITY, COORDINATION AND

GOVERNANCE A DECADE AFTER ITS CREATION

Ms Diane Fromage, researcher, Marie Sklodowska-Curie fellow, Siences Po

- IV. THE FUTURE OF EUROPE: WHY DO WE NEED A SECOND

CHAMBER IN THE EUROPEAN UNION?

Mr Guillaume Sacriste, Senior Lecturer, University Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, CESSP

- I. INTRODUCTION

- SESSION 4

CONSTITUTIONS, SOVEREIGNTY AND EUROPEAN LAW

- I. INTRODUCTION:

Mr Jean-François Rapin, Chaiman of the European affairs Committee of the French Senate

- II. CONSTITUTIONAL IDENTITY AND THE COURT OF

JUSTICE OF THE EUROPEAN UNION

Ms Laure Clément-Wilz, Professor of public law at the university of Paris-Est Créteil, France

- III. THE POLISH CONSTITUTIONAL COURT AND THE

EUROPEAN UNION

Mr Andràs Jakab, Professor of constitutional and administrative law at the university of Salzburg

- IV. CONSTITUTIONAL CORE AREAS AND EUROPEAN LAW:

GERMAN EXPERIENCES

Mr Mattias Wendel, Professor of public law at the university of Leipzig

- V. SEEKING SOLUTIONS TO CONFLICTS BETWEEN NATIONAL

IDENTITIES AND EUROPEAN RULES AND PRINCIPLES

Mr Bertrand Mathieu, Professor of public law at the University of Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, State Councillor in extraordinary service

- I. INTRODUCTION:

- CLOSING OF PROCEEDINGS

Mr Jean-François Rapin,

Chairman of the European affairs committee

of the French Senate

N° 168

SÉNAT

SESSION ORDINAIRE DE 2023-2024

Enregistré à la Présidence du Sénat le 5 décembre 2023

RAPPORT D'INFORMATION

FAIT

au nom de la commission des affaires

européennes (1) relatif aux actes du

colloque sur le rôle

des parlements nationaux

dans l'Union européenne organisé au

Sénat le 6 décembre

2021,

Par M. Jean-François RAPIN,

Sénateur

(1) Cette commission est composée de : M. Jean-François Rapin, président ; MM. Alain Cadec, Cyril Pellevat, André Reichardt, Mme Gisèle Jourda, MM. Didier Marie, Claude Kern, Mme Catherine Morin-Desailly, M. Georges Patient, Mme Cathy Apourceau-Poly, M. Louis Vogel, Mme Mathilde Ollivier, M. Ahmed Laouedj, vice-présidents ; Mme Marta de Cidrac, M. Daniel Gremillet, Mmes Florence Blatrix Contat, Amel Gacquerre, secrétaires ; MM. Pascal Allizard, Jean-Michel Arnaud, François Bonneau, Mme Valérie Boyer, M. Pierre Cuypers, Mmes Karine Daniel, Brigitte Devésa, MM. Jacques Fernique, Christophe-André Frassa, Mmes Annick Girardin, Pascale Gruny, Nadège Havet, MM. Olivier Henno, Bernard Jomier, Mme Christine Lavarde, MM. Dominique de Legge, Ronan Le Gleut, Mme Audrey Linkenheld, MM. Vincent Louault, Louis-Jean de Nicolaÿ, Teva Rohfritsch, Mmes Elsa Schalck, Silvana Silvani, M. Michaël Weber.

AVANT-PROPOS

Mesdames, Messieurs,

A quelques mois des prochaines élections européennes et à l'heure où la perspective d'un nouvel élargissement de l'Union européenne appelle à en réformer le fonctionnement institutionnel, la présente publication des actes du colloque sur le rôle des parlements nationaux dans l'Union européenne, organisé le 6 décembre 2021 au Sénat, peut utilement contribuer aux débats qui s'ouvrent.

C'est à la veille du premier semestre 2022, au cours duquel la France assumait la présidence tournante du Conseil de l'Union européenne, et en pleine Conférence sur l'avenir de l'Europe - tenue du 9 mai 2021 au 9 mai 2022 - que la commission des affaires européennes du Sénat a monté ce colloque, afin de faire, sous l'angle essentiellement universitaire, un point sur la montée en puissance des parlements nationaux dans la construction européenne. Depuis le début des années 1990, ces derniers se sont effectivement vus reconnaître un rôle croissant dans l'Union européenne, alors que le déficit démocratique a semblé parallèlement se creuser à mesure que les compétences de l'Union se sont étendues à la faveur des crises successives - zone euro en 2010, crise migratoire en 2015, pandémie en 2021, agression de l'Ukraine en 2022- : au cours des dernières décennies, il a ainsi été décidé de mieux informer les parlements nationaux sur l'activité législative européenne, d'encourager la coopération interparlementaire, de leur confier le contrôle du principe de subsidiarité ou encore de leur permettre un dialogue politique direct avec les institutions européennes. Trente après le début de la mise en place de ces différents dispositifs, le colloque a permis de dresser le bilan de ces outils, d'étudier le développement de la coopération interparlementaire et d'analyser, dans une logique comparative, les prérogatives dont disposent les parlements nationaux vis-à-vis de leur gouvernement. Il a également permis d'éclairer le débat actuel sur la conciliation entre l'identité constitutionnelle et l'appartenance à l'Union européenne, qui prend de l'ampleur et rappelle que les parlements nationaux sont les pierres angulaires de l'édifice européen.

Convaincue par ce colloque qu'une meilleure implication des parlements nationaux dans le jeu institutionnel européen peut contribuer à rendre l'Union européenne plus démocratique, la commission des affaires européennes du Sénat a prolongé sa démarche en lançant un groupe de travail sur ce sujet, au sein de la Conférence des organes spécialisés dans les affaires de l'Union (COSAC) à laquelle trois de ses membres participent ainsi que trois députés français, avec leurs homologues des 26 autres parlements nationaux de l'Union et six membres du Parlement européen. J'ai eu l'honneur de conduire les travaux de ce groupe au premier semestre 2022, au titre de la présidence française, et la satisfaction de parvenir en juin 2022 à l'adoption, par consensus entre les parlementaires membres du groupe de travail, d'un rapport1(*) comportant des propositions innovantes susceptibles de renforcer le rôle des parlements nationaux dans l'Union européenne. Certaines ne nécessitent pas de révision des traités et pourraient donc faire l'objet d'une mise en oeuvre par simple décision des institutions concernées, ce à quoi je ne cesse d'appeler.

Ces actes du colloque du 6 décembre 2021 attestent par ailleurs que les parlements nationaux se trouvent dans des positions très diverses à l'égard de leur exécutif et qu'obtenir une meilleure reconnaissance de leur rôle européen ne constitue pas pour chacun d'eux un défi de même envergure. Je plaide donc parallèlement pour qu'au sein de notre propre pays, le rôle du Parlement national en matière européenne soit valorisé et pour que sa mission de contrôle de l'action européenne du Gouvernement soit consolidée. Ce point mériterait également d'être débattu dans les prochains mois, qui seront cruciaux pour la vie démocratique européenne.

Jean-François Rapin

Président de la commission des affaires européennes du Sénat

FOREWORD

Ladies and gentlemen,

A few months before the next European elections and at a time when the prospect of a further enlargement of the European Union calls for a reform of its institutional functioning, the present publication of the proceedings of the symposium on the role of national parliaments in the European Union, held on 6 December 2021 at the French Senate, can make a useful contribution to the debates that are about to begin.

It was on the eve of the first half of 2022, during which France assumed the rotating presidency of the Council of the European Union, and in the midst of the Conference on the Future of Europe - held from 9 May 2021 to 9 May 2022 - that the French Senate's Committee on European affairs organised this symposium in order to take stock, essentially from an academic perspective, of the growing importance of national parliaments in European integration. Since the early 1990s, national parliaments have been given a growing role in the European Union, while at the same time the democratic deficit has seemed to widen as the Union's competences have been extended by successive crises - the euro zone in 2010, the migratory crisis in 2015, the pandemic in 2021, and the aggression of Ukraine in 2022. Over the last few decades, decisions have been taken to keep national parliaments better informed about European legislative activity, to encourage interparliamentary cooperation, to entrust them with monitoring the principle of subsidiarity, and to allow them direct political dialogue with the European institutions. Thirty years after the introduction of these various mechanisms, the symposium provided an opportunity to take stock of these tools, to study the development of interparliamentary cooperation and to analyse, from a comparative perspective, the prerogatives enjoyed by national parliaments vis-à-vis their governments. It also shed light on the current debate on reconciling constitutional identity and membership of the European Union, which is gaining momentum and serves as a reminder that national parliaments are the cornerstones of the European edifice.

Convinced by this symposium that a better involvement of national parliaments in the European institutional game can contribute to making the European Union more democratic, the French Senate's European affairs Committee has extended its approach by launching a working group on this subject, within the Conference of Parliamentary Committees for Union Affairs of Parliaments of the European Union (COSAC), in which three of its members participate, as well as three members of the French National Assembly, with their counterparts from the 26 other national parliaments of the Union and six members of the European Parliament. I had the honour of leading the work of this group in the first half of 2022, under the French Presidency, and the satisfaction of achieving in June 2022 the adoption, by consensus between the parliamentary members of the working group, of a report[1] containing innovative proposals likely to strengthen the role of national parliaments in the European Union. Some of these proposals do not require a revision of the Treaties and could therefore be implemented by a simple decision of the institutions concerned, which is what I keep calling for.

These proceedings of the symposium of 6 December 2021 also show that the national parliaments are in very different positions with regard to their executive and that obtaining greater recognition of their European role is not a challenge of the same scale for all of them. I would therefore make a parallel plea for the role of the national parliament in European matters to be enhanced within our own country and for its role in scrutinising the government's European action to be consolidated. This point also deserves to be debated in the coming months, which will be crucial for the democratic life of Europe.

Jean-François Rapin

Chair of the European affairs committee of the French Senate

PROGRAMME DU COLLOQUE

SYMPOSIUM PROGRAMME

9 h 15 - OUVERTURE / OPENING

· M. Gérard Larcher, Président du Sénat / President of the Senate

9 h 30 - 11 h 00 - SESSION 1

Le contrôle parlementaire de la politique européenne des gouvernements /

Parliamentary scrutiny of governments' European policy

· Introduction / Introduction : M. Jean-François Rapin, Président de la commission des affaires européennes du Sénat français, Chairman of the European Affairs Committee of the French Senate

· Modératrice / Moderator : Mme Diane Fromage, chercheuse individuelle Marie Sklodowska-Curie à Sciences Po, Marie Sklodowska-Curie researcher at Sciences Po

Circuits nationaux de contrôle parlementaire dans l'UE : panorama des principales tendances et lacunes existantes (National circuits of parliamentary scrutiny of EU affairs : towards a convergence of the srutiny models?)

· Mme Elena Griglio, fonctionnaire du Sénat italien, professeure associée à l'université Luiss Guido Carli de Rome, Parliamentary senior official of the Italian Senate and adjunct professor at Luiss Guido Carli university in Rome

Le contrôle parlementaire de la politique européenne du gouvernement en France : tendances et évolutions (Parliamentary scrutiny of the French governments' European policy: trends and developments)

· M. Didier Blanc, professeur de droit public à l'Université Toulouse 1 Capitole, Professor at Toulouse 1 Capitole University for research in European, international and comparative law (IRDEIC)

Le contrôle parlementaire de la politique européenne du gouvernement en Suède : le rôle de la commission des affaires européennes du Parlement suédois (Parliamentary scrutiny of the Swedish governments' European policy: The role of the EU Committee in the Swedish Parliament)

· Mme Johanna Möllerberg Nordfors, cheffe du secrétariat de la commission pour l'Union européenne du Parlement suédois, head of the secretariat of the European Union committee of the Swedish Parliament

Comment rendre le contrôle parlementaire de la politique européenne plus efficace ? Avantages et inconvénients du système danois (How to make parliamentary scrutiny more efficient? Advantages and disadvantages of the Danish system)

· Mme Lotte Rickers Olesen, représentante du Parlement danois auprès des institutions européennes, Permanent Representative of the Danish Parliament to the European Union

11 h 30 - 13 h 00 - SESSION 2

Le rôle des parlements nationaux dans le processus décisionnel européen

The role of national parliaments in the European decision-making process

· Introduction / Introduction : M. Pierre Laurent, Vice-Président de la commission des affaires européennes du Sénat français, Deputy Chair of the European affairs committee of the French Senate

· Modératrice / Moderator : Mme Diane Fromage, chercheuse individuelle Marie Sklodowska-Curie à Sciences Po, Marie Sklodowska-Curie researcher at Sciences Po

Les interactions entre les parlements nationaux et les institutions de l'Union européenne : un panorama (Interactions between national Parliaments and the European institutions: an overview)

· M. Olivier Rozenberg, professeur associé à Sciences Po, professor, Sciences po, centre for European studies and comparative politics

Parlements nationaux : comment passer d'un pouvoir de veto à un rôle proactif ? (How can national parliaments move on from a role of veto player to a proactive role?)

· Mme Katrin Auel, professeure associée à l'Institut d'études avancées de Vienne, associate professor at the Institute for advanced studies in Vienna

Les conséquences pour les Parlements nationaux du rôle croissant de l'Union européenne sur les sujets d'union économique et monétaire et les moyens de s'y adapter (The consequences for national parliaments of the increasing role of the EU on EMU topics and their adaptations)

· M. Gavin Barrett, professeur à l'University college Dublin, professor at the University college of Dublin

Les Parlements nationaux et le processus décisionnel européen pendant l'épidémie de Covid-19 (National parliaments and European decision making during the Covid-19 pandemic)

· Mme Christine Neuhold, professeure à l'Université de Maastricht, Professor at Maastricht University

14 h 30 - 16 h 00 - SESSION 3

La

coopération interparlementaire au niveau de l'Union

Interparliamentary cooperation at Union level

· Introduction / Introduction : M. Didier Marie, Vice-Président de la commission des affaires européennes du Sénat français, Deputy Chair of the European affairs committee of the French Senate

· Modératrice / Moderator : M. Didier Blanc, professeur de droit public à l'Université Toulouse I Capitole, professor of public law at Toulouse I Capitole University

La coopération interparlementaire au niveau politique et administratif, dans le système parlementaire européen (Interparliamentary cooperation at the political and administrative levels, in the Euro-national parliamentary system)

· M. Nicola Lupo, professeur de droit public à l'Université Luiss Guido Carli de Rome, ancien fonctionnaire de la Chambre des députés italienne, professor of public law at Luiss Guido Carli university in Rome

Bilan et futur de la conférence interparlementaire sur la stabilité, la coordination économique et la gouvernance (Assessment and future of the interparliamentary conference on economic stability, coordination and governance a decade after its creation)

· Mme Diane Fromage, chercheuse individuelle Marie Sklodowska-Curie, Marie Sklodowska-Curie researcher at Sciences Po

Futur de l'Europe : pourquoi il faut une seconde chambre au sein de l'Union européenne ? (Future of Europe : why do we need a second Chamber in the EU?)

· M. Guillaume Sacriste, maître de conférences en sciences politiques à l'Université Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne, senior lecturer, university Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, CESSP

16 h 30 - 18 h 00 - SESSION 4

Constitutions, domaine régalien et droit européen

Constitutions, sovereignty and European law

· Introduction / Introduction : M. Jean-François Rapin, Sénateur du Pas-de-Calais, Président de la commission des affaires européennes, Senator for Pas-de-Calais, Chairman of the European Affairs Committee

· Modératrice / Moderator : Mme Diane Fromage, chercheuse individuelle Marie Sklodowska-Curie à Sciences Po, Marie Sklodowska-Curie researcher at Sciences Po

L'identité constitutionnelle et la Cour de justice de l'Union européenne (Constitutional identity and the court of Justice of the European Union)

· Mme Laure Clément-Wilz, professeure de droit public à l'Université Paris Est Créteil, Professor of public law at the University of Paris

Le tribunal constitutionnel polonais et l'Union européenne (The Polish Constitutional Court and the European Union)

· M. András Jakab, professeur de droit constitutionnel et administratif à l'Université de Salzbourg, professor of constitutional and administrative law at the university of salzburg

Domaines constitutionnels essentiels et droit européen : les expériences allemandes (Constitutional core areas and European law: German experiences)

· M. Mattias Wendel, professeur de droit public à l'université de Leipzig, professor of public law at the University of Leipzig

À la recherche de solutions aux conflits entre les identités nationales et les règles et principes européens (seeking solutions to conflicts between national identities and European rules and principles)

· M. Bertrand Mathieu, professeur de droit public à l'Université Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne, Conseiller d'État en service extraordinaire, professor of public law at the University of Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, State councillor in extraordinary service

18 heures

CLÔTURE DES TRAVAUX / CLOSING OF PROCEEDINGS

· M. Jean-François Rapin, sénateur du Pas-de-Calais, Président de la commission des affaires européennes, Senator for Pas-de-Calais, Chairman of the European Affairs Committee

ACTES DU COLLOQUE - VERSION FRANÇAISE

OUVERTURE DU

COLLOQUE :

M. JEAN-FRANÇOIS RAPIN, PRÉSIDENT DE LA

COMMISSION DES AFFAIRES EUROPÉENNES

DU SÉNAT

FRANÇAIS

Mesdames et Messieurs les Sénateurs, mes chers Collègues,

Mesdames et Messieurs les Professeurs et Chercheurs,

Mesdames et Messieurs, ici présents ou connectés à distance,

Je suis très heureux de vous accueillir ce matin au Sénat. Je le fais au nom du Président Larcher qui m'en a confié le soin, car une urgence l'empêche malheureusement d'ouvrir ce colloque comme prévu. Mais la question qui nous réunit aujourd'hui, à savoir « quelle place pour les parlements nationaux dans l'édifice européen ? », est si importante à ses yeux qu'il tient malgré tout à participer à cet événement : il nous rejoindra donc vers midi, et je lui suis d'avance très reconnaissant pour la considération qu'il manifeste ainsi à nos travaux.

Quelle place pour les parlements nationaux dans l'édifice européen ? C'est en effet une interrogation légitime, tant les institutions européennes sont déjà nombreuses. Est-il besoin d'ajouter un acteur dans ce jeu déjà si complexe et difficile à appréhender pour nos concitoyens ? Cette question, nous nous devons de la poser maintenant : d'une part, parce que la conférence sur l'avenir de l'Europe, ouverte en mai dernier, nous invite à réfléchir au fonctionnement de l'Union ; d'autre part, parce que nous sommes à la veille du semestre où la France va se retrouver au coeur de la machinerie européenne, en présidant à son tour le Conseil de l'Union européenne.

La commission des affaires européennes, que j'ai l'honneur de présider, vient de consulter en ligne les élus locaux sur leur perception de l'Union européenne et leur vision de son avenir. Près de 2000 d'entre eux ont participé à cette consultation. Et que nous disent-ils ? Bien sûr, ils associent l'Union européenne à des valeurs positives mais ils la perçoivent d'abord comme une machine bureaucratique et distante, qui ne prête pas suffisamment attention aux territoires dans leur diversité.

C'est justement pour cette raison que les parlements nationaux ont leur place : il ne s'agit pas d'ajouter de la complexité à la complexité, ni des institutions aux institutions. Non ! Et, permettez-moi de « spoiler » ce colloque, comme on dirait d'un film à suspense ou d'une série télévisée, ou de le « divulgâcher », en vous donnant déjà la réponse à la question d'aujourd'hui : ce que l'on attend des Parlements nationaux, c'est qu'ils remettent de la démocratie dans la bureaucratie et donc, in fine, de la légitimité dans la construction européenne. Leur contribution au bon fonctionnement de l'Union européenne a d'ailleurs été progressivement reconnue et consacrée par le traité de Lisbonne.

Oui, mais cette contribution des parlements nationaux, quelle est-elle dans les faits ? La question est passionnante car elle est loin d'être tranchée. Elle mobilise le Sénat de longue date ; vous êtes aussi nombreux à chercher sa réponse. Et je remercie chacun d'entre vous, ici au Sénat ou depuis différents coins d'Europe, d'avoir accepté de nous partager aujourd'hui le fruit de vos réflexions.

Il nous est apparu aujourd'hui que nos interrogations pouvaient s'organiser autour de quatre axes, qui donneront lieu à quatre sessions de notre colloque.

Le premier axe est celui des rapports entre chaque Parlement et son propre Gouvernement, s'agissant de la politique européenne qu'il mène et en particulier des positions qu'il défend au Conseil. Cette question politique est fondamentale car elle opère à deux niveaux :

- d'abord, au niveau national, il est primordial de s'assurer que des champs entiers de l'action du Gouvernement n'échappent pas au contrôle des Parlements nationaux. Après tout, les transferts de souveraineté de l'État vers l'Union peuvent aussi se lire comme des transferts de compétence du Parlement vers le Gouvernement, puisque, dans ces domaines, c'est lui qui pourra décider au Conseil de l'Union européenne - certes collectivement - de ce qui relevait auparavant d'un vote du Parlement ;

- ensuite au niveau communautaire, il s'agit de combler un vide : l'enjeu est d'assurer le contrôle démocratique du Conseil, à travers les gouvernements qui le composent. Pour assurer cette mission, les Parlements nationaux sont irremplaçables : en contrôlant chacun l'action européenne de son gouvernement, tous ensemble, ils démocratisent le fonctionnement du Conseil.

Le deuxième axe est celui du rôle institutionnel que les Parlements nationaux doivent jouer dans l'édifice européen. Il leur a été confié le soin de contrôler le respect du principe de subsidiarité ; puis la Commission leur a ouvert la possibilité plus large d'un dialogue politique direct avec elle, sur tous les volets de son action. C'est incontestablement un progrès ; mais il n'est pas suffisant. Il laisse les Parlements nationaux encore trop en marge du processus de décision européen : il s'agit pour eux de ne pas seulement transposer les directives européennes, mais d'être véritablement associés au processus d'élaboration des textes européens de portée législative.

Le troisième axe de réflexion est celui de l'avenir de la coopération interparlementaire, qui pourrait constituer une nouvelle forme collective de contrôle démocratique de la décision européenne.

Enfin, nous consacrerons la quatrième et dernière session de notre colloque à une tension qui resurgit aujourd'hui entre les parlements nationaux, comme pouvoirs constituants, et la construction européenne. C'est une tension qui est dans la nature même de l'Union, « unie dans la diversité » pour reprendre sa devise ; mais elle prend aujourd'hui une acuité nouvelle, avec les débats qui prospèrent dans plusieurs Etats membres autour de la primauté du droit européen, et du respect de leur identité constitutionnelle.

Je ne m'étends pas plus sur ces deux dernières sessions car le Président Larcher reviendra certainement sur ces sujets puisqu'il interviendra avant que nous les abordions.

SESSION 1

LE

CONTRÔLE PARLEMENTAIRE DE LA POLITIQUE EUROPÉENNE DES

GOUVERNEMENTS

I. INTRODUCTION

M. Jean-François Rapin,

président de la commission des affaires européennes

Je vous propose à présent d'entamer nos travaux et d'ouvrir la première session consacrée au contrôle parlementaire de la politique européenne.

En juin 1992, le Gouvernement de Pierre Bérégovoy échappa à trois voix près à l'adoption d'une motion de censure par l'Assemblée nationale. Cette motion avait été présentée en opposition au soutien qu'il avait apporté au Conseil à la réforme de la politique agricole commune. Cet exemple vient nous rappeler que le Parlement « contrôle l'action du Gouvernement », comme le dit la Constitution, et y compris l'action européenne du Gouvernement. Les positions qu'il défend à Bruxelles ou Luxembourg l'engagent devant le Parlement, à Paris.

Une fois ce principe rappelé, reste à savoir comment faire. Car ce contrôle revêt certaines spécificités. Il y a souvent une asymétrie d'information entre le Parlement et le Gouvernement, qui dispose des projets de textes, mais qui est aussi directement engagé dans les négociations et appréhende donc mieux les rapports de force.

De même, cette activité législative se déroule selon un agenda différent de l'agenda national et avec des acteurs qui sont également différents. C'est ce qui a en particulier justifié la création au Parlement de commissions dédiées aux affaires européennes, pour mieux appréhender ce contexte différent.

La difficulté principale réside peut-être dans le fait que le Conseil fonctionne sur la base de négociations, qui impliquent une part de confidentialité ou de « discussions de couloir », et qui amènent, en fonction de l'équilibre des forces, à faire des concessions si nécessaire. Au demeurant, le Conseil doit également négocier avec le Parlement européen, souvent dans l'opacité des trilogues. Comment, dans ce contexte, identifier précisément la responsabilité d'un Gouvernement ?

L'ensemble des Parlements de l'Union européenne ont dû se confronter à ces difficultés et il est intéressant de noter la diversité des réponses, chacun ayant ses propres traditions parlementaires, son propre droit et son propre système politique.

Je me réjouis que cette première session nous permette d'étudier cette diversité et j'espère que nous pourrons rentrer très concrètement dans les expériences vécues par chaque parlement national : de quelle information chaque parlement national dispose-t-il réellement de la part de son Gouvernement sur les négociations en cours ?

Faut-il par exemple entendre les ministres à huis-clos pour ne pas gêner les négociations ? Le mandat parlementaire de négociation fonctionne-t-il bien ? Nous verrons en particulier comment s'inscrit dans ce cadre le système français et si des améliorations peuvent y être apportées.

II. CIRCUITS NATIONAUX DE

CONTRÔLE PARLEMENTAIRE DANS L'UNION EUROPÉENNE VERS UNE

CONVERGENCE DES MODÈLES DE CONTRÔLE ?

Mme Elena

Griglio, fonctionnaire du Sénat italien, professeure associée

à l'Université Luiss Guido Carli de Rome

1. Introduction. Le circuit national du contrôle parlementaire des affaires européennes et ses effets extraterritoriaux

Je suis extrêmement honorée et heureuse de présenter ma contribution au débat stimulant mené par la commission des affaires européennes du Sénat français sur l'état d'avancement du contrôle parlementaire des questions européennes.

Je voudrais exprimer ma respectueuse gratitude au président Larcher et au président Rapin pour leur aimable invitation. Je félicite la commission, y compris son secrétariat, pour la qualité de ce séminaire et son excellente organisation.

L'objectif de ma présentation est d'analyser, dans une perspective comparative, comment les parlements nationaux interprètent et mettent en oeuvre le contrôle des affaires européennes dans l'interaction nationale avec leurs propres gouvernements.

Cette question repose sur la forme la plus traditionnelle de responsabilité démocratique que l'architecture européenne a dérivée des formes nationales de gouvernement.

En fait, au fil des décennies, chaque parlement national a développé des procédures et des pratiques visant à tenir l'exécutif national responsable de la conduite des affaires européennes. Dans certains parlements, dont ceux des pays nordiques, le contrôle des affaires européennes a une longue histoire et est solidement ancré dans l'interaction entre les pouvoirs législatif et exécutif2(*). D'autres assemblées, en revanche, peuvent être considérées comme des retardataires dans la consolidation du contrôle des affaires européennes en tant que fonction à part entière3(*).

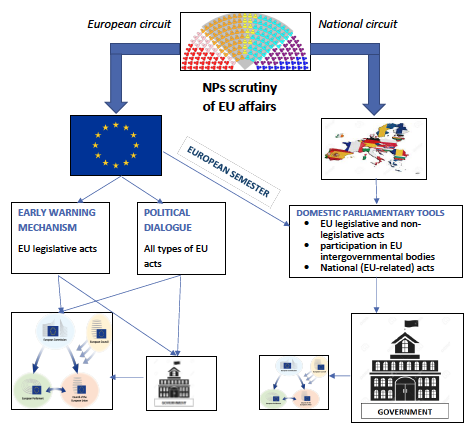

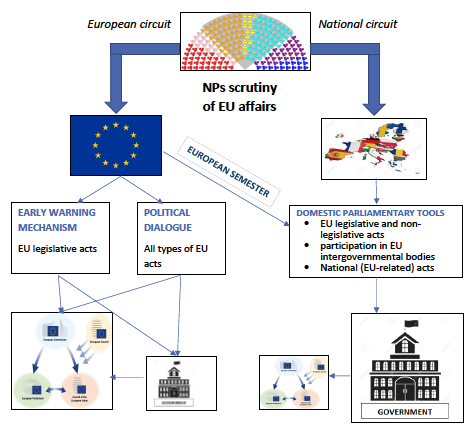

Dans le système parlementaire euro-national actuel4(*), cet ensemble d'interactions nationales ne couvre qu'une partie des procédures qui permettent aux parlements nationaux de participer au processus décisionnel de l'UE. Comme le montre la figure 1, le contrôle parlementaire des affaires européennes se déroule selon deux circuits différents5(*).

D'une part, le circuit européen, par le biais des procédures du mécanisme d'alerte précoce (MEP) et du dialogue politique, permet aux parlements nationaux d'entamer une interaction directe avec les institutions de l'UE sur l'adoption d'actes législatifs et non législatifs de l'UE respectivement6(*). L'objectif principal de cette interaction est de promouvoir la participation des assemblées représentatives nationales dès le début du processus décisionnel. Alors que la Commission européenne est le principal destinataire des avis et décisions parlementaires, ceux-ci peuvent également influencer indirectement les actions de l'exécutif national.

D'autre part, le circuit national offre aux parlements nationaux la possibilité d'activer les outils de contrôle disponibles au niveau national afin d'examiner l'action de l'exécutif dans toutes les sphères d'activité liées à la participation à l'UE, à savoir : l'adoption d'actes législatifs et non législatifs de l'UE, la participation à des organes intergouvernementaux et l'approbation d'actes nationaux (liés à l'UE).

Figure 1 : Circuits européens et nationaux du contrôle parlementaire des affaires européennes

Ces procédures sont capables de soutenir la participation indirecte des législateurs nationaux à toutes les étapes du processus décisionnel de l'UE.

En outre, les effets du circuit national du contrôle parlementaire des affaires européennes ne se limitent manifestement pas au niveau des États membres. En contrôlant les actions de leur propre exécutif, les parlements nationaux sont en mesure de produire des effets « extra-territoriaux », c'est-à-dire d'influencer l'activité des institutions de l'UE et, parallèlement, de renforcer la responsabilité de l'architecture de l'UE7(*) .

Bien qu'il s'agisse d'un circuit potentiellement extrêmement puissant, il est en même temps très dépendant de facteurs nationaux juridiques et politiques, structurels et transitoires8(*).

Sur la base de ces prémisses, cette contribution vise à identifier les facteurs en jeu à la fois au niveau européen et au niveau national, qui influencent les résultats institutionnels associés au circuit national de contrôle des affaires de l'UE. Après avoir expliqué les principales options organisationnelles et procédurales et les modèles primaires qui façonnent l'approche des parlements nationaux en matière de contrôle des affaires européennes, la contribution se concentre sur les deux modèles plutôt divergents de l'Italie et de la Finlande. Ces études de cas ont été sélectionnées afin de montrer comment des parlements ayant des approches radicalement différentes du contrôle des affaires européennes ont récemment connu une convergence, stimulée par les dernières tendances de l'UE, démontrant ainsi comment les développements actuels de l'intégration européenne favorisent une fertilisation croisée des réponses nationales à des besoins institutionnels communs, tels que le contrôle démocratique.

2. Quel impact le contrôle des affaires européennes par les parlements nationaux peut-il avoir ? Les facteurs contextuels européens et nationaux

Afin d'évaluer les effets internes et extraterritoriaux associés au circuit national du contrôle parlementaire des affaires européennes, deux séries de facteurs différents doivent être pris en considération.

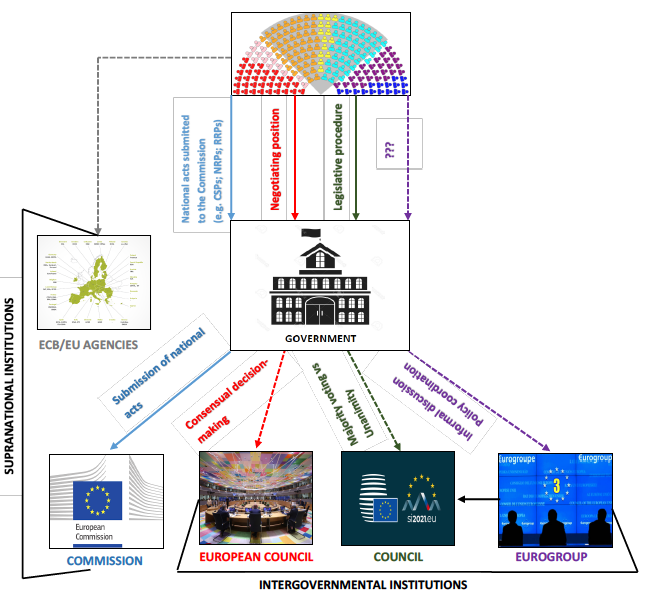

La première série de facteurs dépend de la procédure européenne en question et plus particulièrement de la nature de l'institution européenne concernée.

Figure 2 : Le circuit national du contrôle parlementaire des affaires européennes et son interaction avec les institutions de l'UE

D'une manière générale, le circuit national du contrôle parlementaire est capable de produire ses effets extraterritoriaux les plus forts lorsque des institutions intergouvernementales sont en jeu. En effet, en contrôlant les positions adoptées et les votes exprimés par leur propre exécutif, les parlements nationaux sont en mesure d'influencer indirectement le processus décisionnel au sein du Conseil européen et du Conseil.

La nature de l'influence exercée sur les institutions intergouvernementales dépend d'une série de caractéristiques contextuelles procédurales et institutionnelles différentes.

Premièrement, le type d'impact produit est fortement influencé par les règles de vote qui soutiennent les mécanismes décisionnels européens. L'influence du circuit de contrôle national sur les institutions intergouvernementales de l'UE est la plus forte dans le cas d'une prise de décision à l'unanimité au sein du Conseil, mais elle diminue clairement lorsque le vote à la majorité est adopté. Son effet ne peut être sous-estimé même dans le cas d'une prise de décision consensuelle au sein du Conseil européen9(*).

En outre, parmi les institutions intergouvernementales, l'activité de l'Eurogroupe peut encore être considérée comme une sorte de lacune dans le circuit de la responsabilité. En raison du caractère informel de ses procédures, de son manque de transparence et de l'absence de réels pouvoirs de décision, il est extrêmement difficile pour les parlements nationaux de contrôler les actions menées par leurs propres gouvernements au sein de cet organe10(*).

En revanche, l'impact du circuit de contrôle national sur les institutions supranationales est beaucoup plus faible.

Dans le cas de la Commission, un lien indirect relie cette institution au contrôle national des affaires européennes : il s'agit des mécanismes qui permettent la participation des législateurs nationaux aux procédures conduisant à l'adoption d'actes liés à l'UE. La plupart de ces mécanismes sont ancrés dans les règles et pratiques nationales qui structurent l'interaction entre les pouvoirs législatif et exécutif en ce qui concerne les politiques de l'UE. Les procédures qui impliquent les parlements dans l'adoption des plans nationaux de relance et de résilience (PNRR) en sont un exemple d'actualité. Dans certains cas, la participation des parlements nationaux à ces procédures est directement étayée par la législation de l'UE, comme dans le cas de l'adoption des programmes nationaux de réforme et des programmes de stabilité ou de convergence dans le cadre du semestre européen11(*).

D'autres institutions supranationales - y compris la Banque centrale européenne et les agences de l'UE - ne relèvent absolument pas de l'interaction entre les parlements nationaux et leurs gouvernements nationaux dans le domaine des affaires européennes. Au contraire, les parlements nationaux sont en mesure d'initier une interaction directe - non médiatisée par l'exécutif - avec ces institutions, par exemple par le biais d'auditions ou de débats parlementaires.

Outre les mécanismes décisionnels de l'UE, l'autre facteur qui influence les résultats institutionnels du circuit de contrôle national est lié aux différentes capacités des parlements à contrôler et à lier leurs gouvernements dans la sphère des affaires européennes. Par exemple, ce n'est que dans certains États membres (y compris les pays nordiques qui suivent le modèle du « mandatement » - voir infra) que le gouvernement est formellement tenu de respecter les instructions parlementaires et que les parlements ont activé des mécanismes de contrôle interne capables d'englober toute sphère potentielle d'activité de l'UE initiée par l'exécutif.

Les différences de performance et d'efficacité du circuit national de contrôle au niveau national dépendent de facteurs à la fois juridiques et pré-juridiques.

En particulier, cinq facteurs déterminants semblent jouer un rôle majeur : premièrement, l'architecture institutionnelle nationale, comprenant la forme de gouvernement, l'interaction exécutif/législatif et la force interne du parlement par rapport aux autres branches12(*) ; deuxièmement, les pouvoirs formels de l'UE conférés au parlement par la Constitution, les règles de procédure parlementaire, la législation statutaire, les conventions et pratiques internes, et leurs arrangements13(*) ; troisièmement, l'environnement politique, résultant de la politique des partis, de la relation entre l'exécutif et le parti, et des rôles de la majorité et de l'opposition au Parlement14(*) ; quatrièmement, l'inclination individuelle à l'examen des affaires européennes, visible à travers les orientations du rôle des députés, les motivations, les interactions avec les électeurs et la proximité ou la distance par rapport aux questions européennes15(*) ; et cinquièmement, les facteurs contextuels, y compris la coïncidence temporelle avec une situation d'urgence telle que la crise de la zone euro, le Brexit ou la crise de Covid-1916(*).

La combinaison de ces déterminants juridiques et pré-juridiques influence fortement le type d'approche développé par chaque parlement national dans le contrôle de la conduite exécutive des politiques de l'UE. Cependant, indépendamment des variations nationales, plusieurs facteurs communs semblent permettre de concevoir le contrôle des affaires européennes comme une fonction autonome et distincte.

3. Comment les parlements nationaux façonnent le contrôle des affaires européennes : les principales options disponibles

Comme nous l'avons remarqué dans les sections précédentes, le contrôle parlementaire des affaires européennes dans le circuit national identifie une fonction relationnelle qui s'adresse formellement au gouvernement national. En même temps, il a également une portée extraterritoriale, ce qui se traduit par une influence indirecte sur les institutions de l'UE et par des effets secondaires potentiels produits en relation avec d'autres parlements nationaux.

Bien que cette fonction soit autonome, elle est néanmoins interconnectée avec les autres fonctions parlementaires "traditionnelles", notamment l'élaboration des lois, le contrôle et la définition des orientations politiques. Ce lien explique pourquoi le contrôle des affaires européennes s'effectue par le biais d'un large éventail d'outils et de procédures parlementaires nationaux, allant de la collecte d'informations ou de rapports exécutifs aux déclarations et débats gouvernementaux, et des auditions et enquêtes à la mise en question ou au vote de résolutions et de motions.

La figure suivante(3) explique les différentes variables qui déterminent le contrôle des affaires européennes en tant que fonction parlementaire.

|

Base juridique |

Base constitutionnelle |

Règles et procédures infra-constitutionnelles |

Pratiques informelles |

|

Objet |

Contrôle sur pièces (propositions législatives et non législatives de l'UE) |

Contrôle de la procédure (y compris sur la base d'un mandat) |

Contrôle des actes nationaux (liés à l'UE) (par exemple, les DSP, les PNR, les PRR) |

|

Calendrier |

Examen ex ante · phase pré-législative · avant la réunion intergouvernementale concernée · avant l'adoption de l'acte national (lié à l'UE) |

Contrôle continu · dans le cadre de la procédure législative, après la publication de la proposition · pendant la réunion · dans le processus national d'adoption d'un acte lié à l'UE |

Contrôle a posteriori |

|

Organe de contrôle |

Commission des affaires européennes (ou équivalent) |

Affaires européennes et commissions sectorielles |

Plénière |

|

Résultats parlementaires |

Mandats/résolutions |

Transparence/débat |

Influence informelle |

|

Rôle des partis |

Consensuel |

Clivage traditionnel majorité/opposition |

Forte compétition |

Figure 3 : Les principales variables qui influencent le contrôle des affaires européennes par les parlements nationaux

Le contrôle des affaires européennes peut trouver son fondement juridique dans la Constitution elle-même, ou dans des sources de droit sous-constitutionnelles - de la législation statutaire aux règles et procédures parlementaires -, généralement intégrées par des pratiques informelles.

Trois types de contrôle différents peuvent être activés au niveau national : le contrôle sur pièces17(*) donne aux parlements la possibilité d'examiner et de débattre des propositions législatives et non législatives de l'UE avant leur adoption formelle par les institutions de l'UE ; le contrôle procédural (qui comprend les approches basées sur le mandat18(*) ) permet aux législatures de superviser ex ante et aussi ex post la participation de leur gouvernement au processus décisionnel de l'UE, y compris lors des réunions du Conseil et du Conseil européen ; enfin, le contrôle des actes nationaux (liés à l'UE) implique les parlements dans le processus d'adoption de toutes les décisions et de tous les actes nationaux qui sont fondés sur la gouvernance européenne, y compris le Semestre européen ou la gouvernance de relance.

Indépendamment du type de contrôle activé, trois options principales sont offertes aux parlements, leur permettant de s'engager dans un contrôle ex ante (qui peut affecter la phase pré-législative de l'UE, la phase précédant la réunion intergouvernementale pertinente ou la formation de l'acte national), dans un contrôle continu (dans le cas où le parlement intervient après la publication d'une proposition législative, pendant la réunion intergouvernementale ou pendant le processus décisionnel national déterminant pour l'adoption d'un acte national lié à l'UE) ou dans un contrôle ex post.

En ce qui concerne l'organisation interne de cette fonction, le contrôle des affaires européennes s'effectue généralement au sein des commissions des affaires européennes (ou équivalentes), des commissions des affaires européennes et des commissions sectorielles ou en séance plénière19(*) .

Si l'on se concentre sur les résultats potentiels, le contrôle parlementaire peut aboutir à l'adoption de positions et de décisions formelles, soutenues par le vote de mandats contraignants ou de résolutions non contraignantes.

Si les mandats contraignants sont en mesure d'assurer un contrôle formel de l'action exécutive au niveau de l'UE, jusqu'à la stipulation d'instructions de vote explicites, les mécanismes de contrôle non contraignants offrent au parlement la possibilité d'exercer une influence politique sur le gouvernement. Cela est particulièrement vrai dans le cas des chambres hautes, dont l'indépendance par rapport au continuum entre le gouvernement et sa majorité parlementaire donne la possibilité d'exprimer des opinions et des préoccupations indépendantes. Avant le Brexit, le contrôle des questions européennes par la Chambre des Lords britannique était un exemple central de ce type d'influence « douce » sur l'exécutif20(*).

Dans de nombreux cas, cependant, les procédures de contrôle peuvent ne pas aboutir à un résultat formel ; dans ce cas, leur objectif premier est de promouvoir la transparence et un débat pluraliste sur la conduite des affaires de l'UE par l'exécutif.

Enfin, le style de la politique des partis - qu'elle soit consensuelle, prenant la forme traditionnelle d'un clivage entre majorité et opposition, ou fortement concurrentielle - est un autre élément qui influence fortement la mise en oeuvre du contrôle des questions européennes au niveau parlementaire.

Les parlements nationaux ont combiné ces options alternatives de manière assez originale.

Pour expliquer ces multiples combinaisons, la littérature a élaboré d'autres classifications des modèles de contrôle nationaux21(*). L'une des classifications les plus explicites distingue cinq catégories progressives de responsables du contrôle des affaires européennes, comme suit : les retardataires en matière de contrôle désignent les parlements moins impliqués dans les affaires européennes ; les forums publics sont les parlements qui ont tendance à débattre des affaires européennes principalement en séance plénière, à la fois ex ante et ex post, donc avec une plus grande transparence, mais avec un niveau de spécialisation et d'attention aux questions techniques moins élevé ; les chiens de garde des gouvernements sont les assemblées qui examinent les affaires européennes à la fois en commission et en séance plénière, mais principalement dans la phase ex post ; les décideurs politiques sont les parlements qui abordent les questions européennes principalement dans la phase ex ante, soit dans les affaires européennes, soit dans les commissions sectorielles ; enfin, les experts traitent les affaires européennes de manière hautement professionnelle et spécialisée, en développant une forte expertise ex ante par le biais du travail en commission.

Les sections suivantes analysent ces catégories de manière diachronique.

4. Modèles de contrôle dans une perspective dynamique : comment les parlements nationaux réagissent aux changements majeurs dans le cadre de l'UE

Les catégories générales identifiées pour expliquer les différences initiales entre les modèles de contrôle nationaux doivent être considérées dans une perspective dynamique afin d'évaluer la manière dont elles tendent à s'adapter aux changements continus du cadre contextuel.

En effet, les quinze dernières années ont été marquées par une intense fertilisation croisée des expériences nationales, favorisée par plusieurs tendances en cours22(*). Il s'agit du renforcement du dialogue entre les assemblées représentatives, grâce à l'initiation du mécanisme d'alerte précoce et du dialogue politique et à l'intensification de la coopération interparlementaire, ainsi que de la détermination, en réponse à la crise de la zone euro, de la nouvelle gouvernance économique, qui renforce le rôle européen des parlements nationaux dans le Semestre européen. En outre, les crises (zone euro, Brexit, migration et Covid-19) que l'UE a connues au cours des deux dernières décennies ont contribué à la mise en oeuvre d'ajustements politiques et institutionnels au niveau des États membres, ce qui s'est souvent traduit par un rapprochement des modèles nationaux.

a) Comparaison de deux modèles de contrôle alternatifs : les cas finlandais et italien

Le rapprochement des modèles nationaux de contrôle est le mieux illustré par les expériences de l'Italie et de la Finlande. J'ai choisi ces références en me référant aux différences originelles entre les deux modèles ainsi qu'à la transformation qu'ils ont récemment subie.

Historiquement, les parlements finlandais et italien ont représenté les prototypes de deux manières divergentes d'aborder les questions européennes, enracinées dans des modèles et des traditions de contrôle qui, d'un point de vue comparatif, peuvent être considérés comme les deux pôles opposés du cadre européen.

Cependant, au cours des quinze dernières années, ces deux modèles ont connu une sorte de convergence basée sur l'hybridation de leurs caractéristiques traditionnelles par l'introduction d'outils et de pratiques dérivés de l'autre prototype.

La figure 4 présente une synthèse des différences originales entre les deux expériences parlementaires.

|

FINLANDE |

ITALIE |

|

|

Base juridique |

Une base constitutionnelle solide (articles 47, 96 et 97 de la Constitution) |

Base juridique subconstitutionnelle (L. 11/2005, remplacée par L. 234/2012 ; règlement intérieur du Parlement) |

|

Type de contrôle |

Examen approfondi des documents et des mandats · Accès illimité à l'information · Rapports gouvernementaux · Déclarations de la commission · Débats plutôt sporadiques lors des sessions plénières |

Avant Lisbonne : modèle faible basé sur des documents (réserves d'examen rarement utilisées) Après Lisbonne : · le MEF intensifie l'examen fondé sur des documents · l'introduction d'un contrôle de procédure en plénière, en s'adressant au Conseil européen + renforcement du contrôle des actes nationaux (liés à l'UE) |

|

Calendrier |

Ex ante (dès les premières étapes de la formulation de la politique) En cours (pendant les négociations/réunions législatives) Ex post (après les réunions) |

Examen des documents : le plus souvent en cours (après la publication de la proposition législative), rarement au stade pré-législatif. Contrôle procédural : ex ante Contrôle des actes nationaux (liés à l'UE) : ex ante |

|

Organe de contrôle |

Centralité des commissions : rôle important de la Grande Commission, complété par les commissions des affaires étrangères et les commissions sectorielles. Participation limitée de la plénière, principalement pour les débats axés sur la « haute politique » (et non pour les décisions). |

Examen des documents : participation occasionnelle des commissions permanentes (en fonction de l'importance politique de la question) Contrôle de la procédure : implication systématique de la plénière (Conseil européen) Examen des actes nationaux (liés à l'UE) : en commission et en séance plénière |

|

Résultats parlementaires |

Déclarations de la commission avec un mandat contraignant |

Résolutions des commissions ou de la plénière (non contraignant ou moyennement contraignant) |

|

Rôle des partis |

Style consensuel (« parler d'une seule voix à tous les niveaux de la prise de décision à Bruxelles ») Rôle actif de l'opposition dans les travaux des commissions |

Les affaires européennes tendent à suivre le clivage traditionnel majorité/opposition Relativement peu de débats idéologiques partisans |

Figure 4 : Comparaison entre le contrôle finlandais et italien des affaires européennes

D'une part, la Finlande - un retardataire dans l'intégration de l'UE - offre un exemple de contrôle rigoureux des affaires européennes23(*). Cette fonction est ancrée dans la Constitution et, depuis l'adhésion de la Finlande aux Communautés européennes, elle a été soutenue par un document solide et un contrôle basé sur le mandat. Quatre atouts principaux expliquent la solidité de l'implication de l'Eduskunta dans l'élaboration des politiques de l'UE24(*).

La première force peut être identifiée dans les dispositions constitutionnelles qui reconnaissent formellement le rôle du parlement et de ses commissions dans le contrôle des affaires européennes, en réglementant leur participation à la préparation nationale des questions relatives à l'Union européenne (article 96) et leurs droits à l'information (article 97).

Après son adhésion à la Communauté européenne, l'Eduskunta a décidé de ne pas créer une commission spéciale des affaires européennes, mais de s'appuyer sur une commission préexistante, la Grande Commission, en tant qu'organe central chargé de coordonner la position du Parlement sur les questions européennes. Ce choix a été formellement adopté dans la Constitution.

Le deuxième point fort du modèle de contrôle finlandais est l'accès illimité aux informations détenues par les autorités publiques dont bénéficient le parlement et ses commissions pour l'examen de toutes les questions pertinentes, y compris les affaires européennes.

La réduction des asymétries d'information représente un outil fondamental pour promouvoir la responsabilité du Gouvernement dans une sphère d'action fortement imprégnée par la domination de l'exécutif.

Les droits d'information du Parlement concernant les questions européennes sont spécifiquement mentionnés et réglementés par les articles 96 et 97 de la Constitution. Ces prérogatives sont toutefois complétées par le droit général - reconnu par les articles 4425(*) et 46 de la Constitution - de recevoir les rapports du cabinet, ainsi que le rapport annuel du gouvernement sur ses activités.

Ces mécanismes permettent aux députés d'être informés en temps utile de la conduite des affaires européennes par les organes exécutifs.

L'efficacité et la continuité de l'échange d'informations entre le gouvernement et le parlement est une condition préalable pour déterminer le moment du contrôle parlementaire. En effet, sa capacité à couvrir l'ensemble du processus décisionnel constitue une autre force. L'Eduskunta intervient dès les premières étapes de la formulation des politiques, ce qui offre aux députés la possibilité d'identifier, dès le départ, les questions potentiellement controversées et de dire au gouvernement comment les aborder au niveau européen. Le dialogue entre le parlement et le gouvernement suit ensuite toutes les négociations intergouvernementales et l'ensemble du processus législatif.

Les auditions ministérielles ont lieu au sein de la Grande Commission avant la réunion du Conseil, lorsque cela est nécessaire, et immédiatement après. La régularité de cet échange de vues et d'opinions a considérablement amélioré le dialogue entre l'Eduskunta et le gouvernement, renforçant la coordination des politiques, stimulant la responsabilité de l'exécutif dans la gestion des questions européennes et renforçant la capacité du parlement à influencer la prise de décision.

Ce qui rend le contrôle finlandais des affaires européennes si incroyablement efficace, c'est le rôle de ses commissions. Cette fonction de contrôle est assurée par la Grande Commission, complétée par la Commission des affaires étrangères et par les autres commissions permanentes spécialisées26(*).

Ces derniers suivent les questions européennes et font rapport à la Grande Commission en lui soumettant leurs orientations. Sur la base de ce travail préliminaire et des informations reçues par le gouvernement, la Grande Commission peut rédiger une déclaration qui devient politiquement contraignante pour l'exécutif.

Dans le modèle de contrôle finlandais d'origine, l'essentiel du contrôle des affaires européennes était donc confié aux commissions, tandis que les débats publics en plénière jouaient un rôle marginal. Le travail en commission offrait la possibilité de coopérer de manière informelle, favorisant un dialogue bipartisan fructueux, ainsi que la participation active de l'opposition à la formulation de la politique nationale de l'UE.

La nature prédominante de l'Eduskunta en tant que « parlement de travail » explique donc également l'approche consensuelle traditionnellement adoptée pour façonner le traitement des questions européennes27(*) . Le pragmatisme, la coopération entre les partis, l'absence de divisions partisanes et de débats idéologiques sont les attitudes dominantes qui ont caractérisé la coordination nationale des questions européennes. Leur principal objectif était de faciliter l'obtention d'un consensus, afin que la Finlande puisse « parler d'une seule voix à tous les niveaux de la prise de décision à Bruxelles »28(*) (sur les dernières évolutions de ce modèle, voir 4.2).

D'autre part, le cas italien donne un aperçu de l'expérience d'un pays qui, bien qu'étant l'un des fondateurs des Communautés européennes, a toujours manqué d'une tradition de contrôle des affaires européennes comparable aux normes établies par l'Europe du Nord29(*). La législation a été la réponse dominante à la gestion des affaires européennes et ce n'est qu'au cours des quinze dernières années, grâce à la conjonction de facteurs européens et nationaux, que l'Italie a également été en mesure de définir un rôle pour le parlement dans le contrôle des affaires européennes30(*).

La faiblesse historique du législateur italien dans ce domaine va de pair avec l'absence de référence constitutionnelle au contrôle parlementaire des questions européennes31(*). Les lois statutaires et les règles de procédure parlementaire ont partiellement tenté de combler cette lacune, mais dans le cadre pré-Lisbonne, le contrôle parlementaire a continué à suivre un modèle faible basé sur des documents, n'impliquant qu'une utilisation extrêmement modeste de l'outil des réserves parlementaires.

L'entrée en vigueur du traité de Lisbonne a donné lieu à de nouvelles formes d'engagement institutionnel du Parlement italien dans l'examen des questions européennes et dans la participation au processus décisionnel de l'UE32(*).

D'un point de vue juridique, la nécessité de se conformer au cadre institutionnel révisé de l'UE a été principalement satisfaite par l'approbation de la loi n° 234/2012, « Règles générales sur la participation de l'Italie à la formation et à la mise en oeuvre de la législation et des politiques de l'Union européenne »33(*) . Cette loi a été suivie par les deux chambres, principalement par le biais d'actes et de pratiques « internes »34(*), qui n'ont été traduits en modifications formelles du règlement intérieur que par la chambre haute, le Sénat.

Le Parlement italien, dans l'ère post-Lisbonne, a connu la consolidation du contrôle documentaire et du contrôle procédural, qui ont toutefois suivi - au moins jusqu'à la fin de 2021 - des procédures et des mécanismes assez différents de ceux du modèle nordique.

L'intensification de l'examen des affaires européennes sur la base de documents peut être considérée comme l'une des principales adaptations au mécanisme d'alerte précoce. Dans les deux chambres, le contrôle repose sur le rôle des commissions permanentes sectorielles et de la commission des affaires européennes. Son calendrier, qui commence dès la publication de la proposition législative, tend à suivre les négociations législatives à Bruxelles. Les cas de contrôle pré-législatif dissocié du MEF sont extrêmement rares.

L'examen sur pièces se termine par l'adoption d'une résolution de la commission, qui est soumise à l'examen du gouvernement. D'un point de vue juridique, ces actes ne sont pas contraignants pour l'exécutif. Il est donc extrêmement difficile de déterminer leur influence sur la gestion des affaires européennes par l'exécutif.

Parallèlement, la loi n° 234/2012 a favorisé l'engagement structurel des plénières des deux chambres le contrôle l'examen préliminaire de l'action gouvernementale avant les réunions du Conseil européen. La procédure commence par une déclaration du président du Conseil des ministres ou du ministre délégué devant les deux chambres, exposant la position à adopter lors de la réunion du Conseil européen ; cette déclaration est suivie d'un débat et se termine par l'adoption d'une ou de plusieurs résolutions. Ces résolutions comprennent généralement de grandes orientations politiques pour l'exécutif, qui sont convenues entre le Gouvernement et sa majorité parlementaire.

La combinaison de ces mécanismes confirme que le contrôle parlementaire italien des affaires européennes après Lisbonne a évolué vers un modèle hybride ancré dans le rôle de la plénière pour le contrôle procédural et dans le travail en commission pour le contrôle documentaire. Le résultat de l'implication parlementaire (jusqu'aux dernières innovations législatives - voir 4.2) a été l'adoption de résolutions qui ne lient pas le gouvernement d'un point de vue juridique, mais qui doivent être encadrées et interprétées dans le contexte de l'interaction politique entre l'exécutif et le législatif.

D'un point de vue politique, l'Italie se caractérise traditionnellement par une orientation clairement pro-européenne, tant dans l'opinion publique que dans le système politique35(*). Malgré la montée des positions eurosceptiques au sein de certains partis de centre-droit36(*), le Parlement a continué à enregistrer un niveau d'implication significativement faible et un taux de politisation réduit des questions européennes37(*).

Les débats et les décisions sur les questions d'actualité de l'UE tendent à suivre le clivage entre la majorité et l'opposition et donnent lieu à relativement peu de débats idéologiques partisans38(*), car les questions européennes en elles-mêmes sont rarement perçues comme des sujets de discorde.

b) Adaptations actuelles des modèles de contrôle finlandais et italien : vers une convergence ?

Les changements majeurs apportés à la gouvernance de l'Union européenne par les crises de la zone euro39(*) et de Covid-1940(*) ont fortement influencé les pratiques et les mécanismes de contrôle des parlements finlandais et italien.

D'une part, l'approche finlandaise du contrôle des affaires européennes a commencé à subir une transformation majeure dans le contexte de la crise de la zone euro. Plusieurs facteurs ont stimulé ce changement, notamment : la propagation des sentiments anti-européens parmi les électeurs ; le succès écrasant du Parti eurosceptique finlandais aux élections parlementaires de 2011 ; la transition vers un gouvernement de coalition ; et le durcissement de la politique finlandaise en matière d'adhésion à l'UE. Ce climat politique différent a profondément influencé le travail de l'Eduskunta, rompant avec le style consensuel traditionnel et favorisant l'apparition de formes d'opposition. L'impact de ces tendances sur les procédures de contrôle parlementaire a conduit à un changement du cadre du débat, qui est passé des sessions des commissions aux réunions plénières, où des divisions marquées et des critiques des actions du Gouvernement sont apparues41(*).

Les décisions de la commission, traditionnellement adoptées de manière consensuelle, ont commencé à indiquer une dépendance à l'égard des procédures de vote à la majorité. L'opposition a commencé à faire un usage intensif des opinions dissidentes parallèlement à l'adoption des déclarations de la Grande Commission.

La politisation des questions européennes à laquelle l'Eduskunta finlandaise a été confrontée dans le contexte de la crise de la zone euro s'est encore développée au cours de la crise de Covid-19. Les procédures activées par l'Eduskunta en rapport avec les différents instruments du plan de relance indiquent un changement général dans le débat, qui est passé de l'atmosphère de travail informelle des commissions à l'environnement plus ouvert et compétitif des sessions plénières, où la confrontation entre les forces politiques devient souvent rude et âprement disputée42(*).

La commission du droit constitutionnel a elle-même demandé, à titre de garantie, un vote en plénière à la majorité des deux tiers43(*) pour l'approbation des trois principales décisions concernant le plan de relance : la décision relative aux ressources propres44(*), le cadre financier pluriannuel 2021-202745(*) et l'instrument de relance et de résilience46(*).

Ce cadre procédural n'a pas empêché les forces minoritaires de constituer une forte opposition à ces décisions, motivée par une critique radicale de l'action du gouvernement47(*). Dans le cas du CFP et du mécanisme de relance, l'opposition est allée jusqu'à activer des formes d'obstructionnisme parlementaire qui ont suscité une grande inquiétude au niveau européen également48(*). En outre, les partis minoritaires ont continué à faire un usage intensif des opinions dissidentes et des résolutions, tant en plénière qu'en commission49(*).

Dans l'ensemble, la crise pandémique a poursuivi et accentué le changement de paradigme qui, depuis la crise de la zone euro, a progressivement dépassé le style consensuel et parlementaire traditionnel qui caractérisait auparavant l'approche de l'Eduskunta en matière d'affaires européennes.

D'autre part, les transformations subies par le contrôle parlementaire italien des affaires européennes dans le contexte de la crise de la zone euro et de la crise de la Covid-19 semblent suivre une direction complémentaire à celle de l'Eduskunta.

Outre les exemples de contrôle documentaire et procédural développés dans les deux chambres après le traité de Lisbonne, de nouvelles pratiques d'implication parlementaire dans le contrôle des actes nationaux (liés à l'UE) ont commencé à se répandre dans la nouvelle architecture du semestre européen et de la gouvernance de la relance.

Le semestre européen a encouragé la participation du Parlement italien à l'adoption des programmes nationaux de réforme et de stabilité, qui sont examinés dans le cadre du document économique et financier, qui est le plan macroéconomique général fixant les priorités et les orientations pour le prochain cycle de finances publiques. Les procédures de contrôle imposent un rôle d'information et de rapport aux commissions budgétaires des deux chambres, tout en attribuant un rôle important au débat en séance plénière, qui se conclut par l'approbation d'une résolution majoritaire autorisant formellement le gouvernement à soumettre les programmes nationaux de réforme et de stabilité à la Commission de l'UE.

Une procédure assez similaire a soutenu la participation du Parlement italien à l'adoption du plan national de relance et de résilience. Même si le plan de relance européen ne fait aucune référence au rôle des parlements nationaux50(*), le Parlement italien a été l'un des plus proactifs dans le contrôle de l'activité exécutive à différents stades de l'élaboration et de l'adoption du PNRR. Les deux chambres italiennes font partie des quelques assemblées impliquées dans les trois étapes suivantes : dans le contrôle ex post des lignes directrices pour la rédaction du PNRR51(*) ; dans le contrôle ex post du projet de plan52(*) ; et dans le contrôle ex ante du plan final. Les deux premières étapes ont impliqué à la fois la commission et la plénière53(*).

En ce qui concerne la phase de mise en oeuvre, deux dispositions statutaires ont formellement reconnu le rôle de contrôle du parlement dans la surveillance de l'exécution des projets du PNR et le maintien du calendrier convenu avec les institutions de l'UE. Ce rôle est exclusivement assumé par les commissions permanentes, dont les prérogatives d'information ont été renforcées afin de soutenir la formulation d'observations et d'évaluations susceptibles d'améliorer la mise en oeuvre du PNRR54(*) . En outre, les commissions permanentes sont impliquées dans l'examen des rapports semestriels sur la mise en oeuvre du PNRR soumis par le gouvernement : sur la base d'une enquête approfondie55(*), la procédure peut s'achever par l'adoption de résolutions adressant des orientations politiques au gouvernement sur les faiblesses détectées au cours de la phase de mise en oeuvre.

Les pratiques initiées dans le cadre du Semestre européen et de la gouvernance de relance ont donc confirmé une nouvelle place pour le parlement dans le contrôle des actes (nationaux) liés à l'UE, avec un rôle de pilotage attribué aux commissions.

Entre-temps, la loi européenne 2019-2020 (loi du 23 décembre 2021, n° 238) a fortement renforcé les mécanismes de contrôle procédural du Parlement italien, en introduisant officiellement certains outils typiques du modèle nordique.